Rail transport in India

Rail transport is a commonly used mode of long-distance transportation in India. Almost all rail operations in India are handled by a state-owned organisation, Indian Railways, Ministry of Railways. The rail network traverses the length and breadth of the country, covering a total length of 63,140 kilometres (39,233 mi).[1] It is said to be the 4th largest railway network in the world,[2] transporting over 6 billion passengers and over 350 million tonnes of freight annually.[1] Its operations cover twenty-eight states and three union territories and also provide limited service to Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Both passenger and freight traffic has seen steady growth, and as per the 2009 budget presented by the Railway Minister, the Indian Railways carried over 7 billion passengers in 2009

Railways were introduced to India in 1853,[3] and by the time of India's independence in 1947 they had grown to forty-two rail systems. In 1951 the systems were nationalised as one unit—Indian Railways—to form one of the largest networks in the world. The broad gauge is the majority and original standard gauge in India; more recent networks of metre and narrow gauge are being replaced by broad gauge under Project Unigauge. The steam locomotives have been replaced over the years with diesel and electric locomotives.

Locomotives manufactured at several places in India are assigned codes identifying their gauge, kind of power and type of operation. Colour signal lights are used as signals, but in some remote areas of operation, the older semaphores and disc-based signalling are still in use. Accommodation classes range from general through first class AC. Trains have been classified according to speed and area of operation. All trains are officially identified by a four-digit code, though many are commonly known by unique names. The ticketing system has been computerised to a large extent, and there are reserved as well as unreserved categories of tickets.

Contents |

History

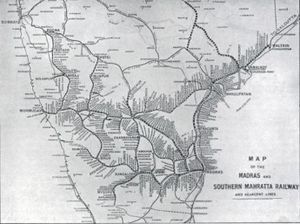

A plan for a rail system in India was first put forward in 1832. The first rail line of the Indian sub-continent came up near Chintadripet Bridge (presently in Chennai) in Madras Presidency in 1836 as an experimental line.[4][5] In 1837, a 3.5-mile long rail line was established between Red Hills and stone quarries near St. Thomas Mount.[6] In 1844, the Governor-General of India Lord Hardinge allowed private entrepreneurs to set up a rail system in India. The East India Company (and later the British Government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to five percent during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99 year lease, with the government having the option to buy them earlier.[7]

Two new railway companies, Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR) and East Indian Railway (EIR), were created in 1853-54 to construct and operate two 'experimental' lines near Bombay and Calcutta respectively.[7] The first train in India had become operational on 22 December 1851 for localised hauling of canal construction material in Roorkee.[8] A year and a half later, on 16 April 1853, the first passenger train service was inaugurated between Bori Bunder in Bombay and Thane. Covering a distance of 34 kilometres (21 mi), it was hauled by three locomotives, Sahib, Sindh, and Sultan.[9]

In 1854 Lord Dalhousie, the then Governor-General of India, formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India. Encouraged by the government guarantees, investment flowed in and a series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion of the rail system in India.[10] Soon various native states built their own rail systems and the network spread to the regions that became the modern-day states of Assam, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh. The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 kilometres (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 kilometres (15,842 mi) in 1880 - mostly radiating inland from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.[11] Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies. The railway line from Lahore to Delhi was done B.S.D. Bedi and Sons (Baba Shib Dayal Bedi), this included the building of the Jamuna Bridge. By 1895, India had started building its own locomotives, and in 1896 sent engineers and locomotives to help build the Uganda Railway.

At the beginning of the twentieth century India had a multitude of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks.[12] In 1900 the government took over the GIPR network, while the company continued to manage it. With the arrival of the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and foodgrains to the port city of Bombay and Karachi en route to UK, Mesopotamia, East Africa etc. By the end of the First World War, the railways had suffered immensely and were in a poor state.[13] In 1923, both GIPR and EIR were nationalized with the state assuming both ownership and management control.[12]

The Second World War severely crippled the railways as rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were converted into munitions workshops.[14] After independence in 1947, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated as a single unit, which was christened as the Indian Railways. The existing rail networks were abandoned in favour of zones in 1951 and a total of six zones came into being in 1952.[12]

As the economy of India improved, almost all railway production units were 'indigenised' (produced in India). By 1985, steam locomotives were phased out in favour of diesel and electric locomotives. The entire railway reservation system was streamlined with computerisation between 1987 and 1995.

In 2003, the Indian Railways celebrated 150 years of its existence. Various zones of the railways celebrated the event by running heritage trains on routes similar to the ones on which the first trains in the zones ran. The Ministry of Railways commemorated the event by launching a special logo celebrating the completion of 150 years of service.[15][16] Also launched was a new mascot for the 150th year celebrations, named "Bholu the guard elephant".[17]

Locomotives

Indian Railways use a specialised classification code for identifying its locomotives. The code is usually three or four letters, followed by a digit identifying the model (either assigned chronologically or encoding the power rating of the locomotive).[18] This could be followed by other codes for minor variations in the base model.

The three (or four) letters are, from left to right, the gauge of tracks on which the locomotive operates, the type of power source or fuel for the locomotive, and the kind of operation the locomotive can be used for.[18] The gauge is coded as 'W' for broad gauge, 'Y' for metre gauge, 'Z' for the 762 mm narrow gauge and 'N' for the 610 mm narrow gauge. The power source code is 'D' for diesel, 'A' for AC traction, 'C' for DC traction and 'CA' for dual traction (AC/DC). The operation letter is 'G' for freight-only operation, 'P' for passenger trains-only operation, 'M' for mixed operation (both passenger and freight) and 'S' for shunting operation. A number alongside it indicates the power rating of the engine.[18] For example '4' would indicate a power rating of above 4,000 hp (2,980 kW) but below 5,000 hp (3,730 kW). A letter following the number is used to give an exact rating. For instance 'A' would be an additional 100 horsepower (75 kW); 'B' 200 hp (150 kW) and so on. For example, a WDM-3D is a broad-gauge, diesel-powered, mixed mode (suitable for both freight and passenger duties) and has a power rating of 3400 hp (2.5 MW).

The most common diesel engine used is the WDM-2, which entered production in 1962. This 2,600 hp (1.9 MW) locomotive was designed by Alco and manufactured by the Diesel Locomotive Works, Varanasi, and is used as a standard workhorse.[19] It is being replaced by more modern engines, ranging in power up to 4,000 hp (3 MW).

There is a wide variety of electric locomotives used, ranging between 2,800 to 6,350 hp (2.1 to 4.7 MW).[19] They also accommodate the different track voltages in use. Most electrified sections in the country use 25,000 volt AC, but railway lines around Mumbai use the older 1,500 V DC system.[20] Thus, Mumbai and surrounding areas are the only places where one can find AC/DC dual locomotives of the WCAM and WCAG series. All other electric locomotives are pure AC ones from the WAP, WAG and WAM series. Some specialised electric multiple units on the Western Railway also use dual-power systems. There are also some very rare battery-powered locomotives, primarily used for shunting and yard work.

The only steam engines still in service in India operate on two heritage lines (Darjeeling and Ooty), and on the tourist train Palace on Wheels.[21] Plans are afoot to re-convert the Neral-Matheran to steam. The oldest steam engine in the world in regular service, the Fairy Queen, operates between Delhi and Alwar.

Signalling systems

The Indian Railways makes use of colour signal lights, but in some remote areas of operation, the older semaphores and discs-based signalling (depending on the position or colour) are still in use.[22] Except for some high-traffic sections around large cities and junctions, the network does not use automatic block systems. However, the signals at stations are almost invariably interlocked with the setting of points (routes) and so safety does not depend on the skill of the station masters. With the planned introduction of Cab signalling/Anti collision devices the element of risk on account of drivers overshooting signals will also be eliminated.

Coloured signalling makes use of multi-coloured lighting and in many places is automatically controlled. There are three modes:[22]

- Two aspect signalling, which uses a red (bottom) and green (top) lamp

- Three aspect signalling, which uses an additional amber lamp in the centre

- Four (multiple) aspect signalling makes use of four lamps, the fourth is amber and is placed above the other three.

Multiple aspect signals, by providing several intermediate speed stages between 'clear' and 'on', allow high-speed trains sufficient time to brake safely if required. This becomes very important as train speeds rise. Without multiple-aspect signals, the stop signals have to be placed very far apart to allow sufficient braking distance and this reduces track utilisation. At the same time, slower trains can also be run closer together on track with multiple aspect signals.

Semaphores make use of a mechanical arm to indicate the line condition. Several subtypes are used:[22]

- Two aspect lower quadrant

- Three aspect modified lower quadrant

- Multiple aspect upper quadrant

- Disc-based: These signals are located close to levers used to operate points. They are all two-aspect signals.

Production units

The Chittaranjan Locomotive Works in Chittaranjan makes electric locomotives. The Diesel Locomotive Works in Varanasi makes diesel locomotives. The Integral Coach Factory in Perambur makes integral coaches. These have a monocoque construction, and the floor is an integral unit with the undercarriage. The Rail Coach Factory in Kapurthala also makes coaches. The Rail Wheel Factory at Yelahanka manufactures wheels and axles. Some electric locomotives have been supplied by BHEL, Jhansi, and locomotive components are manufactured in several other plants around the country.[18]

Nomenclature

Trains are sorted into various categories that dictate the number of stops along their route, the priority they enjoy on the network, and the fare structure. Each express train is identified by a four-digit number[23]—the first digit indicates the zone that operates the train, the second the division within the zone that controls the train and is responsible for its regular maintenance and cleanliness, and the last two digits are the train's serial number.

For super-fast trains, the first digit is always '2',[23] the second digit is the zone, the third is the division and only the last digit is the serial number within the division. Trains travelling in opposite directions along the same route are usually labelled with consecutive numbers.[23] However, there is considerable variation in train numbers and some zones, such as Central Railway, has a less systematic method for numbering trains.[23] Most express trains also have a unique name that is usually exotic and taken from landmarks, famous people, rivers and so on.[24][25]

Hierarchy of trains

Trains are classified by their average speed.[26] A faster train has fewer stops ("halts") than a slower one and usually caters to long-distance travel.

| Rank | Train | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Duronto Expresses | These are the non-stop point to point rail services (except for operational stops) introduced for the first time in 2009. These trains connects the metros and major state capitals of India and are faster than Rajdhani Expresses. The Duronto services consists of three classes of accommodation namely first AC, two-tier AC, three-tier AC. |

| 2 | Rajdhani Expresses | These are all air-conditioned trains linking major cities to New Delhi. The Rajdhanis have high priority and are one of the fastest trains in India, travelling at about 140 km/h (87 mph). There are only a few stops on a Rajdhani route. |

| 3 | Shatabdi and Jan Shatabdi Expresses | The Shatabdi trains are AC intercity seater-type trains. Jan-Shatabdi trains consists of both AC and non-AC classes. |

| 4 | Super-fast Expresses or Mail trains | These are trains that have an average speed greater than 55 km/h (34 mph). Tickets for these trains have an additional super-fast surcharge. |

| 5 | Express | These are the most common kind of trains in India. They have more stops than their super-fast counterparts, but they stop only at relatively important intermediate stations. |

| 6 | Passenger and Fast Passenger | These are slow trains that stop at most stations along the route and are the cheapest trains. The entire train consists of the General-type compartments. |

| 7 | Suburban trains | Trains that operate in urban areas, usually stop at all stations. |

Suburban rail

Many cities have their own dedicated suburban networks to cater to commuters. Currently, suburban networks operate in Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Delhi, Hyderabad, Pune and Lucknow-Kanpur. Hyderabad, Pune and Lucknow-Kanpur do not have dedicated suburban tracks but share the tracks with long distance trains. New Delhi, Kolkata, and Chennai have their own metro networks, namely the New Delhi Metro, the Kolkata Metro,and the Chennai MRTS, with dedicated tracks mostly laid on a flyover.

Suburban trains that handle commuter traffic are mostly electric multiple units. They usually have nine coaches or sometimes twelve to handle rush hour traffic. One unit of an EMU train consists of one power car and two general coaches. Thus a nine coach EMU is made up of three units having one power car at each end and one at the middle. The rakes in Mumbai run on direct current, while those elsewhere use alternating current.[28] A standard coach is designed to accommodate 96 seated passengers, but the actual number of passengers can easily double or triple with standees during rush hour.

Ticketing

India has some of the lowest train fares in the world, and passenger traffic is heavily subsidised by more expensive higher class fares.[29] Until the late 1980s, Indian Railway ticket reservations were done manually. In late 1987, the Railways started using a computerised ticketing system. The entire ticketing system went online in 1995 to provide up to date information on status and availability. Today the ticketing network is computerised to a large extent, with the exception of some remote places. Computerized tickets can be booked for any two points in the country. Tickets can also be booked through the internet and via mobile phones, though this method carries an additional surcharge.

Discounted tickets are available for senior citizens (above sixty years) and some other categories of passengers including the disabled, students, sportspersons, persons afflicted by serious diseases, or persons appearing for competitive examinations. One compartment of the lowest class of accommodation is earmarked for ladies in every passenger carrying train. Some berths or seats in sleeper class and second class are also earmarked for ladies.[30] Season tickets permitting unlimited travel on specific sections or specific trains for a specific time period may also be available. Foreign tourists can buy an Indrail Pass,[31] which is modeled on the Eurail Pass, permitting unlimited travel in India for a specific time period.

For long-distance travel, reservation of a berth can be done for comfortable travel up to 90 days prior to the date of intended travel.[30] Details such as the name, age and concession (if eligible) are required and are recorded on the ticket. The ticket price usually includes the base fare, which depends on the classification of the train (example: super-fast surcharge if the train is classified as a super-fast), the class in which one wishes to travel and the reservation charge for overnight journeys.

If a seat is not available, then the ticket is given a wait listed number; else the ticket is confirmed, and a berth number is printed on the ticket. A person receiving a wait listed ticket will have to wait until there are enough cancellations to enable him to move up the list and obtain a confirmed ticket.[30][31] If his ticket is not confirmed on the day of departure, he may not board the train. Some of the tickets are assigned to the RAC or Reservation against Cancellation, which is between the waiting list and the confirmed list.[30][31] These allow the ticket holder to board the train and obtain an allotted seat decided by a ticket collector, after the ticket collector has ascertained that there is a vacant (absentee) seat.

Reserved Railway Tickets can be booked through the website of Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation Limited,[32] and also through mobile Phones and SMS. Tickets booked through this site are categorised in to iTickets and eTickets. iTickets are those, which are booked by a passenger and then printed and delivered to the passenger for carrying during journey. eTickets are those, which the passenger can print himself at his end and carry while travelling. While traveling on an eTicket, one needs to carry one of the authorised valid Photo Identity Cards. Cancellation of eTickets are also done online, without the requirement for the passenger to go to any counter. Unreserved tickets are available for purchase on the platform at any time before departure. An unreserved ticket holder may only board the general compartment class. All suburban networks issue unreserved tickets valid for a limited time period. For frequent commuters, a season pass (monthly or quarterly) guarantees unlimited travel between two stops.

International links

India has rail links with Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh.[33] It also plans to install a rail system in southern Bhutan. A move to link the railways of India and Sri Lanka never materialised.

Before the Partition of India there were eight rail links between what are now India and Pakistan. However, currently there are only two actively maintained rail links between the two countries. The first one is at Wagah in Punjab. The Samjhauta Express plies this route from Amritsar in India to Lahore in Pakistan.[33] The second one, opened in 2006 runs between Munabao (in Rajasthan in India) and Khokhrapar (in Sindh in Pakistan). Other discused links are Ferozepur–Samasata, Ferozepur–Lahore, Amritsar–Lahore, Amritsar–Sialkot and Jammu–Sialkot.[33][34]

After the creation of East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), many trains that used to run between Assam and Bengal had to be rerouted through the Chicken's Neck. As of March 2010, there exists one passenger link between India and Bangladesh, the Maitree Express, which plies between Kolkata and Dhaka twice a week.[35] A metre gauge link exists between Mahisasan (Mohishashon) and Shahbazpur. Another link is between Radhikapur and Birol. These two links are used occasionally for freight.[33][34] A rail link between Akhaura in Bangladesh and Agartala in India has also been proposed.[36][37]

There are two links between India and Nepal: Raxaul Jn., Bihar–Sirsiya, Parsa and Jaynagar, Bihar–Khajuri, Dhanusa.[34] The former is broad gauge, while the latter is narrow gauge.

Private railways

Though the Indian Railways enjoys a near monopoly in India, a few private railways do exist, left over from the days of the Raj, usually small sections on private estates, etc. There are also some railway lines owned and operated by companies for their own purposes, by plantations, sugar mills, collieries, mines, dams, harbours and ports, etc. The Bombay Port Trust runs a BG railway of its own, as does the Madras Port Trust.[38] The Calcutta Port Commission Railway is a BG railway. The Vishakhapatnam Port Trust has BG and NG, 2 ft 6 in (762 mm), railways.

The Bhilai Steel Plant has a BG railway network.[38] The Tatas (a private concern) operate funicular railways at Bhira and at Bhivpuri Road (as well as the Kamshet–Shirawta Dam railway line, which is not a public line). These are not common carriers, so the general public cannot travel using these. The Pipavav Rail Corporation holds a 33-year concession for building and operating a railway line from Pipavav to Surendranagar.[38] The Kutch Railway Company, a joint venture of the Gujarat state government and private parties, is involved (along with the Kandla Port Trust and the Gujarat Adani Port) to build a Gandhidham–Palanpur railway line.[38] These railway lines are principally used to carry freight and not for passenger traffic.

Although generally IR has decided the freight tariffs on these lines, recently (February 2005) there have been proposals to allow the operating companies freedom to set freight tariffs and generally run the lines without reference to IR.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Salient Features of Indian Railways". Indian Railways. http://www.indianrail.gov.in/abir.html. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ↑ "CIA — The World Factbook -- Country Comparison :: Railways". CIA. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2121rank.html. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ↑ "Indian Railways in Postal Stamps". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/articles/vikas/stamps.html. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ↑ "A railwayman recalls". The Hindu Business Line. 2005-09-09. http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/life/2005/09/09/stories/2005090900050300.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ "Opening up new frontiers". The Hindu Business Line. 2006-10-27. http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/2006/10/27/stories/2006102700310900.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ "Heritage consciousness". The Hindu. 2004-01-26. http://www.hindu.com/mp/2004/01/26/stories/2004012600270300.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 1–19. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ "First train ran between Roorkee and Piran Kaliyar". National News. The Hindu. 2002-08-10. http://www.hinduonnet.com/2002/08/10/stories/2002081000040800.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ↑ Babu, T. Stanley (2004). "A shining testimony of progress". Indian Railway Board. p. 101.

- ↑ Thorner, Daniel (2005). "The pattern of railway development in India". In Kerr, Ian J.. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 80–96. ISBN 0195672925.

- ↑ Hurd, John (2005). "Railways". In Kerr, Ian J.. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–172–96. ISBN 0195672925.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 44–52. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ Awasthi, Aruna (1994). History and development of railways in India. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 181–246.

- ↑ Wainwright, A. Marin (1994). Inheritance of Empire. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 9780275947330. http://books.google.com/?id=1wERzXx94c8C&pg=PA48.

- ↑ "Celebrating 150 years". The Hindu. http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl2117/stories/20040827003811200.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ "In full steam". The Hindu. http://www.hindu.com/thehindu/mp/2002/04/15/stories/2002041500480100.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ "Bholu the Railways mascot unveiled". Times of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/7099051.cms. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Locomotives — General Information – I". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-loco.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Diesel and Electric Locomotive Specifications". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-specs.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ Paranjape, Shirish (December 2000). "The Nomenclature System of Locomotives on IR". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/articles/loco-nomenclature.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ "Palace On Wheels History". aboutpalaceonwheels.com. http://www.aboutpalaceonwheels.com/about-palace-on-wheels/palace-on-wheels-history.html. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Signalling System". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-signal.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "The system of train numbers". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-number.html. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ "Train names". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-name.html. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ Sekhsaria, Pankaj (June 24, 2005). "What's in a Train Name?". The Hindu Business Line. http://www.blonnet.com/life/2005/06/24/stories/2005062400010100.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ↑ "railway operations — I". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-ops.html. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Overview Of the existing Mumbai Suburban Railway". Official webpage of Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation. http://www.mrvc.indianrail.gov.in/overview.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ "[IRFCA] Indian Railways FAQ: Electric Traction — I". Irfca.org. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-elec.html#volt. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ Joshi, V; I. M. D. Little (1996-10-17). "Industrial Policy and Factor Markets". India's Economic Reforms, 1991-2001. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 0198290780. http://books.google.com/?id=r31MYIrISFMC&pg=PA184&dq=indian+rail. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "Reservation Rules". Indian Railways. http://www.indianrail.gov.in/resrules.html. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "General Information on travelling by IR". Travelling by Train in India, IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-travel.html. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation Limited". www.irctc.co.in. http://www.irctc.co.in/. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 "Geography : International". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-inter.html. Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Bhuyan, Mohan. "International Links from India". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/docs/international-links.html. Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ↑ "New schedule for Maitree Express". The Hindu Business Line. 2009-07-25. http://www.blonnet.com/2009/07/25/stories/2009072550721700.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ "India eyes Agartala-Akhaura train service next year". The Daily Star. 2010-02-24. http://www.thedailystar.net/newDesign/latest_news.php?nid=22391. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ "Track Diplomacy". The Times of India. 2010-03-02. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/opinion/edit-page/Track-Diplomacy/articleshow/5629173.cms. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 "Railways other than IR in India". IRFCA.org. Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-nonir.html. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

References

- "IR History: Early Day". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-hist.html. Retrieved 2005-06-19.

- "Zones". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-geog.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Locomotives". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-loco.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Production Units & Workshops". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-shop.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Signalling Systems". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-signal.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Geography : International". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-inter.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Rolling stock". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-stock.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Signal Aspects and Indications – Principal Running Signals". Indian Railways Fan Club. http://www.irfca.org/faq/faq-signal2.html. Retrieved 2005-06-26.

- "Salient Features of Indian Railways". Indian Railways. http://www.indianrail.gov.in/abir.html. Retrieved 2005-06-19.

- "Indian Railways Online Passenger Reservation Site". Indian Railways. http://indianrail.gov.in. Retrieved 2005-06-10.

External links

- Indian Railways Online Official site

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||